“Noh is classical Japanese theatre which combines elements of dance, drama, music and poetry into one highly aesthetic form of art.

On this occasion, I am delighted to welcome the Oshima Noh Theatre, led by Masanobu Oshima, an Important Intangible Cultural Asset as designated

by the Japanese Government, and Theatre Nohgaku, led by Richard Emmert, probably the West’s greatest exponent of this traditional Japanese art form.

The two theatre companies will perform Kiyotsune, a classical noh play, and Pagoda, which is a world premiere of a new play by Jannette Cheong. The latter piece is particularly notable as the performance of the first English-language text written in the noh tradition for performance by a British playwright.

I congratulate them on working hard to realise this unique production of noh performance and wish them every success on their European tour!

”

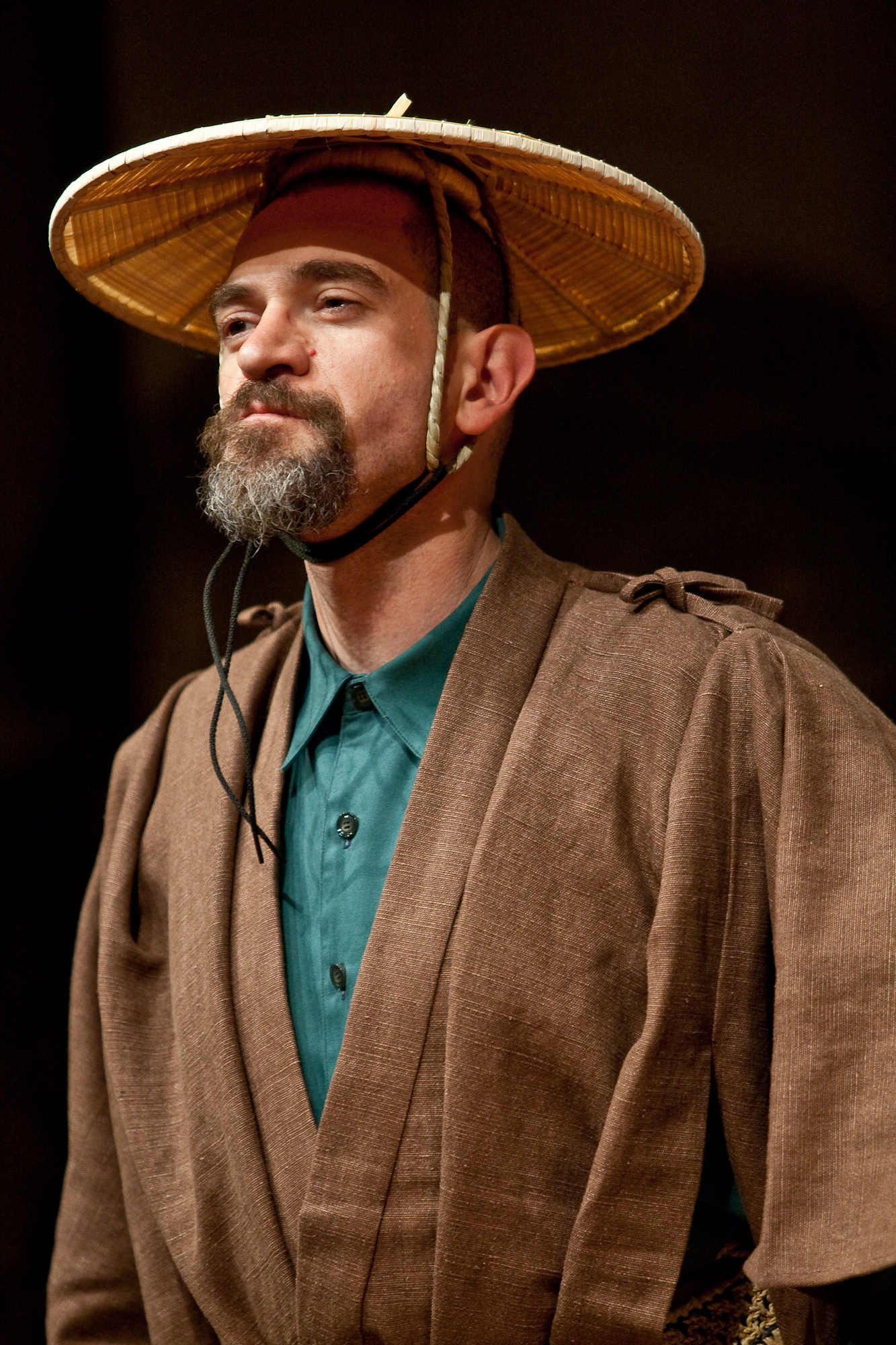

Kinue Oshima

Performing as the nochishite (Act Two, main actor) in Pagoda at the Southbank Centre, London. December 2009.

Photography by Clive Barda

Pagoda

Introduction

The Oshima Noh Theatre of Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan, and Theatre Nohgaku, based in Tokyo and New York, presented, for the first time, a joint production of classical and contemporary noh theatre in the 2009 European tour of Kiyotsune & Pagoda.

This was a rare and unique performance of Japanese noh theatre featuring the classical warrior play Kiyotsune and the world premiere of Pagoda, a new English-language noh play. The production performed in London and Oxford as part of the Japan-UK 150 Festival celebrations, and in Dublin and Paris to complete this two-week tour to Europe.

Pagoda, written by Jannette Cheong, with music by Richard Emmert, founder of Theatre Nohgaku, is a multicultural theatre project that brings together a centuries’ old Japanese theatre tradition and a contemporary British - Chinese story which investigates the themes of identity and migration. This was to be the first time for a strictly English-language noh play to be written by a British playwright and produced in Europe as a fully realised noh performance.

The tour also included ‘Getting to Noh’: a programme of public workshops, lectures, and educational activities to introduce the history, structure, dance, music, costumes and masks of noh.

The Oshima Family, through the Oshima Noh Theatre in Fukuyama, Hiroshima prefecture, has long carried out numerous activities to introduce ‘noh’ to a general Japanese public. Theatre Nohgaku, since 2000, has been striving to introduce English noh to international audiences.

In November 2007, Jannette Cheong went to Fukuyama with a friend, to see one of the regular Oshima Theatre noh performances and was invited to a post-performance party where she met the Oshimas. They, in turn, introduced her to Richard Emmert. Two years later, it is hard to believe that an idea discussed at that party was realised in this unique programme. We were naturally apprehensive about this new venture because it had never been done before.

However, much more, we looked forward to seeing how this original new noh play would be received.

We are extremely grateful to the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs and the many companies and organisations that supported us in realising this large-scale project. We are also convinced that this programme will contribute to the prosperity of noh.

Finally, we would like to express our thanks to everyone engaged in the production for their hard work and cooperation.

Masanobu Oshima, Oshima Noh Theatre Director

Richard Emmert, Theatre Nohgaku Artistic Director

(Adapted from the 2009 Programme Booklet)

Sponsors and contributors to the Pagoda project

2011 Asia Premiere of Takasago & Pagoda at the National Noh Theatre.

Scenes from the classical noh Takasago (han noh) - main actor (shite) performed by Masanobu Oshima; and the English-language noh, Pagoda (in two acts) - main actor (shite) Kinue Oshima, companion actor (nochitsure) Teruhisa Oshima, The Traveller (waki) Jubilith Moore, the Daughter (maetsure) Elizabeth Dowd and the Oyster Fisherman (ai kyogen) Lluis Valls.

Photography by Sohta Kitazawa

Takasago (han noh)

Pagoda (an English-language noh in two acts)

The Theatre Companies

THE OSHIMA NOH THEATRE is based in the Kita school, one of the five main actor noh schools, and features members of the Oshima family, one of the Kita school’s most active traditional noh families. Masanobu Oshima, an important intangible cultural asset as designated by the Japanese government, headed both productions along with his two adult children, Kinue Oshima—one of the few yet highly respected professional female performers in the noh world (and the only female professional performer in the Kita school), and Teruhisa Oshima—an emerging new acting voice in the Kita school in 2009 and now very well-established in the noh world.

THEATRE NOHGAKU is an international company comprised of Japan and North American-based members whose mission is to create and present English language plays in traditional noh style complete with hayashi musicians, masks, costumes and stage sets. Founded and led by Artistic Director Richard Emmert who has spent over 35 years studying, teaching and performing classical Japanese noh in Japan, Theatre Nohgaku serves as a unique cultural and artistic intermediary between Japan and the English-speaking world.

“Autumn leaves drift west and east,

Some paths meet some not,

Untold stories lost in mist, lost in time..”

Jubilith Moore

Performed the role of the Waki (the traveller) in both the European & Asian tours of Pagoda (2009 & 2011)

Photography by Clive Barda

Pagoda Cast & Production Team

An English-language noh in two acts

Author: Jannette Cheong

Director and Composer: Richard Emmert

Choreography: Kinue Oshima, Teruhisa Oshima

Costumes: Teruhisa Oshima, Yasue Ito

Masks: Hideta Kitazawa

Libretto Translation: Pierre Rolle (French), Ryoji Terada (Japanese)

Cast

Shite/Nochishite (MeiIin/Spirit of Meilin) Kinue Oshima

Waki (Young Traveller) Jubilith Moore

Tsure (Daughter/Spirit Daughter) Elizabeth Dowd

Ai (Local Oyster Fisherman) Lluis Valls

Nochitsure (Bai Li/Spirit Son) Teruhisa Oshima

Chorus Leader: Richard Emmert

Chorus: David Crandall, John Oglevee, James Ferner, Matt Dubroff, Ryoji Terada, Greg Giovanni, Tom O’Connor, David Surtasky

Instrumentalists: Narumi Takizawa (Nohkan – flute), Mitsuo Kama (Kotsuzumi – shoulder drum), Eitaro Okura (Otsuzumi – hip drum), Hitoshi Sakurai (Taiko – stick drum)

Production: Yasuko Oshima, Teruhisa Oshima, Jannette Cheong, John Oglevee. Programme, poster & leaflet design: Ken Garland, Anna Carson. The Pine Tree Backdrop: Allan West. Technical Direction: David Surtasky. Photography: Clive Barda, Jannette Cheong, Sohta Kitazawa, David Surtasky.

The Cast of Pagoda and the Chorus performing the world premiere at Southbank Centre, London. December 2009. Photography by Clive Barda.

““Pagoda is a triumph. To have created a new Noh play but retained total authenticity is nothing short of brilliant. It is something that devotees of Noh will savour.””

“It is no mean feat to develop Noh and to write for such an ancient form in another language, but it is incredibly effective. All in all, a very special evening which may have won over a new audience and was certain to delight the converted.”

“....With the benefit of the libretto, the audience could enjoy the lean poetry of Cheong’s words. But combined on stage with the mesmeric effect of chanting voices and slow, understated movement, one was left wondering how so much could be conveyed with such economy of expression....””

““This is just to thank you for enabling a truly wonderful evening to happen. I feel very privileged to have been able to witness such a powerful event. ...I found Pagoda both beautiful and moving, ...and want to congratulate you on so successfully mastering the form and spirit of Noh in such a personal yet universal way, permitting a proper catharsis to take place for the audience.”

“Truly memorable, and moving. A superb form””

“..We thoroughly enjoyed both plays. I was particularly moved by the story in Pagoda which is beautifully written. Having not seen Noh theatre before ... I was really looking forward to the event and was not disappointed. I feel particularly privileged to have had the rare opportunity to have seen it in English.””

““We have seen noh earnestly and brilliantly cross over national borders”

”

““It was a very impressive event. The performance felt authentically “Noh”, despite being in English, and succeeded in giving a Western audience a feeling for the emotional impact of Noh, as well as offering new insights to the Japanese audience. The performances made an important contribution both by updating this ancient art form and also by making it accessible to a wider audience. A fascinating and very worthwhile project.””

““Congratulations for your play!! It was a sad story, very moving! I could never imagine such a story performed as a very historical and traditional Japanese drama. .. Beautiful combination. ...””

“

“I was very impressed to see the English Noh performance. Last time I saw a Noh performance was in 1979. The English performance was very good for modern Japanese because the language is understandable.””

““Thank you again for yesterday, and once again, our congratulations on another successful performance! You have created, as I said last night, a work of great beauty and deep feeling.”

““I would like to congratulate again your Tour in Asia. I really enjoyed Pagoda last night. We are very honoured that SMBCE, our subsidiary in London, is one of the sponsors. Of course, our guests were impressed like me. They also enjoyed last night.”

“From the very first moment I heard the native English speaking female waki’s voice, I thought this noh would be a success. As this piece used noh melodies and stayed very faithful to the classical structure, even without understanding the words, the audience was able to follow the story. Furthermore, this might be the experience that foreigners have when viewing noh for the first time, where they can’t understand the words but get the experience of “feeling” the noh. This shows that foreigners are just as serious as

Japanese in their appreciation of noh. This show gives me hope for the future of noh...”

“The hayashi were all Japanese professionals, but the chorus were all foreigners. It was surprisingly wonderful. Other than the all of the language being in English, it was in every way noh. There was a woman playing the waki and her presence in the wake-za was very powerful and beautiful...

The chorus was sung solidly. They were able to sing strongly in both melodic and dynamic singing styles...

The person playing the shite was an old classmate of mine from Tokyo University of the Arts, Kinue Oshima. She was inspiring...”

Kinue Oshima, Jubilith Moore, Elizabeth Dowd

Performed the roles of the Maeshite (Act One main actor), the Waki (the traveller) and the Tsure (the daughter) in Pagoda in both 2009 & 2011 tours.

Photography by Clive Barda

Pagoda Overview Synopsis

This is a new English-language noh play rooted in the story of the author’s grandmother who sent her youngest son away to sea when he was a young boy to avoid the famine that ravaged China’s rural areas in the 1920s. He never returned.

After his death in London in the 1970s, the author made the journey to China to find her father’s birthplace. Her experiences, at once both tragic and uplifting, are combined with an ancient Chinese legend to form the basis of the play.

A young traveller in search of her father’s roots journeys to his birthplace in Southeast China. Carrying her father’s treasured keepsake, she meets a distraught woman and her daughter in front of an ancient pagoda, lamenting the departure of a young son many years ago. The woman and daughter ‘vanish in the mist’.

Lluis Valls

Performed the role of the Oyster Fisherman in Pagoda (2009, 2011)

The traveller then meets a fisherman who tells her the legend of the Pagoda and of the spirit of Meilin who visits it. The traveller realises her father was the son of Meilin and it was her spirit which she had earlier encountered. As night falls Meilin and daughter appear once more and the traveller presents her father’s keepsake to confirm her identity to them. Lamenting the son’s death they realise that he survived into adulthood and was spared the starvation so many suffered at that time, including Meilin. The presence of the family keepsake enables his spirit to appear and they are united in the spirit world, mother and son, brother and sister. The young traveller is left alone to reflect on the ancient pagoda legend and the migrants’ journey.

SCENE: Autumn 1970s, on the edge of a hamlet in Southeast China.

CATEGORY: Fourth category miscellaneous play, phantasm (mugen) noh in two acts, with taiko stick drum.

Scene by Scene Synopsis

ACT ONE

Stage attendants bring on stage a framework structure representing a pagoda.

1. WAKI ENTRANCE: A traveller enters to shidai music and tells how, after her father’s death, she has decided to travel to his birthplace in China carrying her father’s treasured keepsake. She sings a travel song describing her uncertain quest, the long journey to China, down through the heart of this mysterious and isolated ‘middle kingdom’, and her arrival in the provincial capital and then to her father’s hamlet. She sees a pagoda and decides to ask two approaching women if she can take shelter inside.

2. MAETSURE/MAESHITE ENTRANCE: A peasant mother and daughter enter to issei music and sing of lost souls searching hopelessly, the lament of untold misery saying ‘every grain of rice a tear’, and wondering whether those departed will ever return.

3. WAKI/TSURE/SHITE DIALOGUE: The traveller asks if she may seek shelter in the pagoda. In turn, the mother asks her to count the boats she sees on the horizon and when the traveller reports that there are nine, the mother is disappointed. The daughter explains why her mother is full of sorrow, and invites the traveller to join them to look at the moon from the top of the pagoda. There, the daughter tells how a noblewoman built the pagoda many years ago then narrates the story of how her mother sent her son on a boat to avoid famine but has now waited forty years for his return. The mother once again asks the traveller to count the boats, and is told there are still only nine.

4. MAESHITE/MAETSURE NARRATIVE: The chorus with the daughter and mother sing of the sun setting and waiting for the full moon to rise, then evoke the pain and sorrow one feels and the tears one sheds when separated from loved ones not knowing when, or if, they will ever return.

5. MAESHITE/MAETSURE EXIT: Again the traveller is asked to count the boats on the distant horizon, and this time, as the moon shines brightly, she counts ten. She turns to tell the mother and daughter, but they have vanished.

6. AI INTERLUDE: An oyster fisherman enters singing of the full moon and cold night. He introduces himself as being in charge of the pagoda which is also a lighthouse. He meets the traveller and relates the story of the noblewoman who built the pagoda centuries ago after her husband was lost at sea, and how it is said that her spirit still waits for his return. In turn, the traveller tells how her father recently died and that this is his birthplace. When the fisherman, in sympathy, mentions the local saying “every grain of rice a tear,” the traveller tells how the two women she just met had used the same expression. The fisherman suggests that the two women might have been the spirits of Meilin and her daughter who are also said to visit here. They come to realise that Meilin must be the mother of the traveller’s father, Bai Li, and thus Meilin must be the traveller’s own grandmother.

ACT TWO

7. WAKI WAIT: The traveller reflects on the woman in the ancient story of the Pagoda and that of her grandmother separated from her father, both women waiting for a loved one to return.

8. NOCHISHITE ENTRANCE: The spirit of Meilin enters to deha music singing of the full moon and how the night is longest when there is fear of an empty dawn. She asks the traveller what she seeks, and the Traveller shows her an amulet, the treasured keepsake of her father. Meilin realises it is the one she gave her son when he left home and that he was indeed the traveller’s father.

9. NOCHISHITE NARRATIVE: Meilin reflects on her long wait ending with this news that her son is dead without having returned home. As she laments, the traveller reminds her that he survived to adulthood and with this knowledge, Meilin realises that her long vigil has ended.

10. FINAL DANCE AND EXIT: The presence of the family keepsake enables the spirit of Bai Li to appear. The spirits dance and are united in the spirit world - mother and son, brother and sister. Then, as mother and son exit, the traveller reflects on the many other lost souls in search of one another and wonders what will be revealed as the morning mist clears.

Jannette Cheong/Richard Emmert

Shigeru Nagashima ties the Pagoda nochishite mask on Kinue Oshima. Photography by Sohta Kitazawa

Composing for and directing Pagoda

Composing music for new noh plays demands, in particular, an understanding of noh chant styles and their melodic structure, an understanding of the rhythmic structure and patterns of the drums of the noh ensemble, and an understanding of how sung text fits together with those rhythms. Actually, in the new noh plays being created in Japan, I have never heard of one being composed by a ‘music composer’ - someone trained in composing for a variety of Western or Japanese musical instruments or voice. Rather, those who compose for noh are noh performers themselves, those intimately connected to performing classical noh plays and who understand how music works in those plays.

Composing for noh in English has the added demand that one has to have a sense of how English text can be sung in general, and the imagination to bridge the gap between how a Japanese text can be sung with noh rhythms and how an English text can be sung with noh rhythms. The language characteristics of Japanese and English are different. How can English come to life with noh rhythms without just imitating Japanese?

It is a constant struggle. Certainly I have heard enough criticisms that English does not sound ‘natural’ when sung in noh style. I usually counter that I don’t know of any Japanese speaker going to noh for the first time who thinks that Japanese is necessarily ‘natural’ when sung in noh style. The singing style of noh is a ‘made’, not natural, singing style developed over many centuries. Similarly, with a Western operatic vocal style, there are no doubt those who believe that opera is only natural to Italian and not to any other language. For better or for worse, I have always attempted to find ways for an English text to come to life with a noh score and take on some of the depth of feeling and emotion in the same way I sense happens when I hear Japanese text with the rather ‘unnatural’ musical style of noh.

For Pagoda then, the composing really began as I helped Jannette Cheong structure her piece. Some parts of noh which she adopted have rather straightforward textual and in turn musical structures. Others do not, and in the same way that individual classical noh plays have certain musical characteristics unique to that play and that play alone, Pagoda has certain parts which, though of the noh style, are unique to it.

Thus, having previously composed music for English noh, many of the difficulties for Pagoda in particular remain some of the same difficulties encountered in my earlier compositions. But perhaps most important for me in composing for Pagoda was the fact that Jannette came to understand those musical challenges and was willing to accommodate text changes to fit some musical demands.

Places which she found difficult to change despite my nudging also were good as they forced us both to strive to find yet another way. As these were sung in Theatre Nohgaku’s summer rehearsals in Bloomsburg, Pennsylvania, Jannette made excellent comments and sometimes text changes to make both singing and text develop a tighter and more compact and meaningful fit.

In terms of directing the performance, as I write this from the perspective of two and a half months before the opening, the difficulties are already obvious. Most of Theatre Nohgaku’s members are based in the United States with only four of us in Japan. The Oshima Noh Theatre members and the musicians are all based in Japan. It is clearly a matter of directing long distance as full rehearsals with members from both will not happen until we gather in London in the days just before the December opening.

Allowing such a state might sound a bit optimistic for bringing a new work to the stage. In Japan however, it is standard in traditional performances for performers to prepare a play individually learning from teachers who have already performed it, and then gather for only one rehearsal in advance. For new plays, main performers might gather several times in advance but the practice of having one final rehearsal with all participants is much the same.

For Pagoda , I rehearsed Theatre Nohgaku members in August in the US. Those members are now learning their own parts as I rehearse the Japanese participants in Japan. For TN members used to studying both Japanese and English texts, the English text is certainly easier, but they have less experience in learning a new context of performance. For the Japanese on the other hand, learning a new performance is generally not that difficult except that this one is in English and that changes the equation considerably. Fortunately, all the musicians have worked with Theatre Nohgaku on other plays and they have some idea as to how to match noh rhythms with English. Still they have to memorize a lot of English and I will be working with them to do that.

And finally, for Kinue Oshima, who will sing in English, as an experienced noh performer, her movements will be crisp, clear and centered in the quiet intensity of noh. Learning the English and pronouncing it correctly while singing in the noh style will, however, be new for her. I have every belief that her professionalism in noh will carry her over and the meeting of these two groups on a far away European stage will be an exciting event in the long history of noh.

Richard Emmert, September 2009

Kinue Oshima

Participating in the education work undertaken under the auspices of the Pagoda Project, in association with the Japan Society. September 2009.

Photography by Clive Barda

Theatre Nohgaku Reflects on Pagoda

Theatre Nohgaku reflects on its first European Tour on the TN website

Kevin Salfen, from Theatre Nohgaku, writes in the TN Newsletter in 2012: Pagoda, the work, Pagoda the collaboration: Reflections on the 2011 Asian Tour. (Vol 7, Now 1-2, July 2012)